John Le Carré’s fourth novel, The Looking Glass War, was a satirical rejoinder to all those who had, he felt, got the wrong end of the stick in respect of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. Feeling that they had missed the point that the spy game was a futile, squalid, hopeless affair, he turned the futility, squalor and hopelessness up to 11 to craft a novel that even the least perspicacious reader would realise was a straight up satire. The book was not a critical success and Le Carré later said that ‘readers hated me for it’; they just, he concluded, loved spies too much.

Filming the book was not easy. Published in 1965, it was optioned immediately and spent four years in development hell as various writers, directors and producers tried to wrangle it into a workable script. When it reached the screen in January 1970, it was the third big screen Le Carré adaptation, after The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) and The Deadly Affair (1967), and while it is significantly less successful than its predecessors, there is still a lot to enjoy here.

The film opens with weary British spy Taylor (Timothy West) taking receipt of film from the pilot of a passenger plane (Frederick Jaeger) who has diverted the flight to take aerial photos of a suspected missile installation on the East German border. Taylor grumbles that his bosses won’t even spring for a taxi back to his hotel and so he trudges down a frozen Finnish road in dead of night, carrying the precious film. He is knocked over and killed, and the film rolls away into the snow. It is left ambiguous whether his death was an accident or an assassination.

This incident sets hares running, and aging spymaster Leclerc (a wonderfully dry Ralph Richardson) who misses the glory days of WW2, decides they have to send a man over the border to scope out the supposed installation, which they know of because of some grainy photos bought from a dodgy contact. They hit upon a Pole, Leiser (Christopher Jones), who has jumped ship to be with a young woman who is carrying his child. They promise him he can stay and raise the kid in the UK if he does this job for them, he says yes, and we’re off to the races.

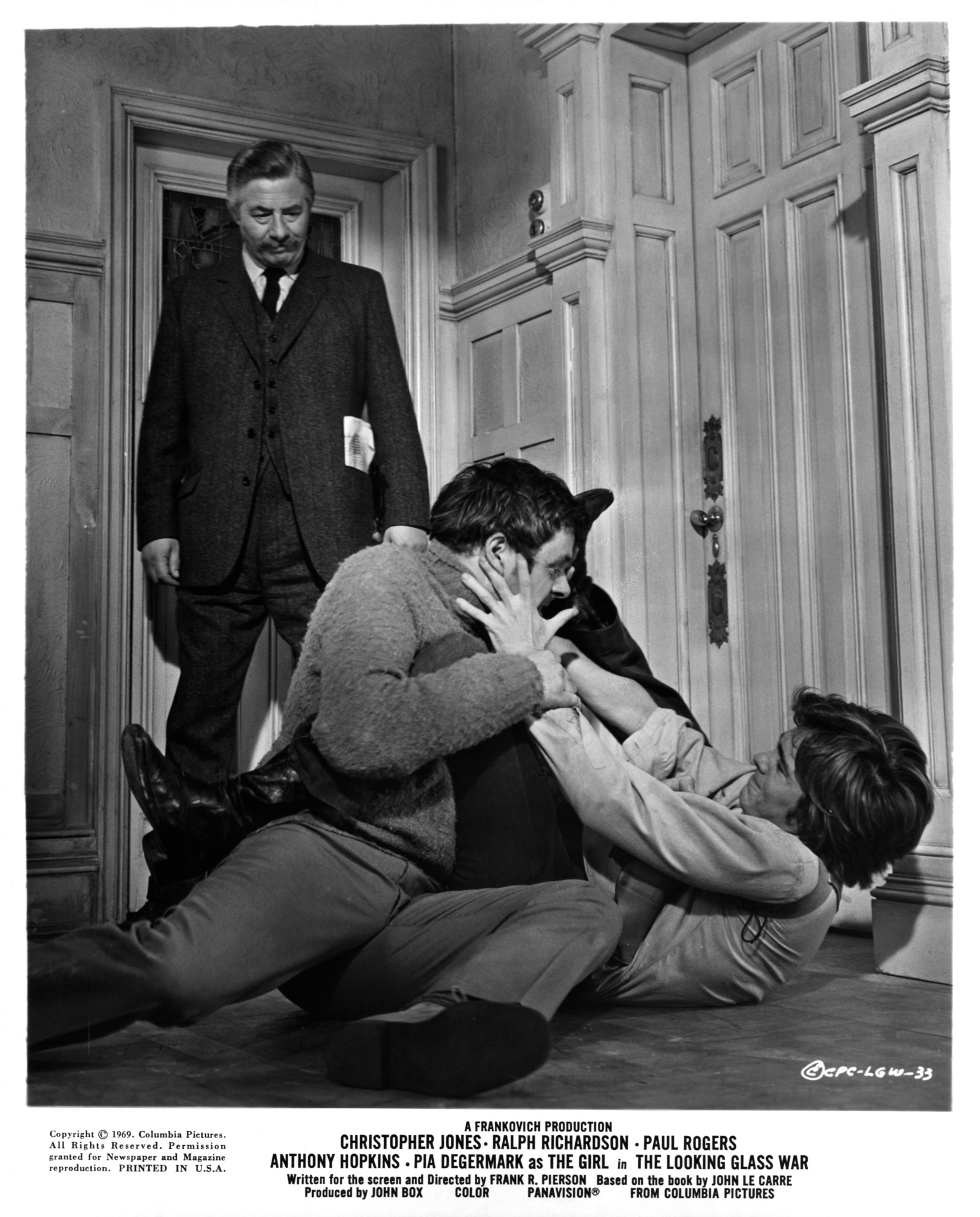

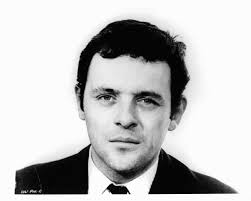

This is a film of two very distinct halves. The first traces the build-up to the mission, Leiser’s recruitment, his backstory, the misgivings of Leclerc’s young protégé Avery (Anthony Hopkins), and the backstage machinations of the old spies whose caper this is. Broadly speaking, this is a watchable and engaging hour. Director Frank Pierson demonstrates a real knack for staging physical action – Taylor’s prolonged death agonies; an awkward , flailing fight between Leiser and Avery; Leiser’s playful kiss-chase seduction of Susan George, who has, unbeknownst to him, aborted his child. It all bodes well for the mission.

Then the mission begins, and despite a thrilling sequence where Leiser crawls through the barbed wire fence and kills a young guard who interrupts him, the film loses focus as Leiser becomes involved with Anna (Pia Degermark, stunning, garlanded with plaudits from her turn in Elvira Madigan).

Anna, who is credited in the opening titles, after four men, merely as The Girl – a little bit on the nose, perhaps? – is one of those female characters who exist only in films of this period. She joins forces with Leiser simply because he is the handsome lead in a spy film. At no point does she display anything even vaguely approximating a believable character with motivations – she is pure plot – and the film withers and dies on the screen every time she appears. Not to mention the fact that the East Germany Leiser infiltrates appears to be some off-kilter communist hybrid of the mind, inhabited by hip young things who dance to Tom Jones in bierkellers.

Anna, who is credited in the opening titles, after four men, merely as The Girl – a little bit on the nose, perhaps? – is one of those female characters who exist only in films of this period. She joins forces with Leiser simply because he is the handsome lead in a spy film. At no point does she display anything even vaguely approximating a believable character with motivations – she is pure plot – and the film withers and dies on the screen every time she appears. Not to mention the fact that the East Germany Leiser infiltrates appears to be some off-kilter communist hybrid of the mind, inhabited by hip young things who dance to Tom Jones in bierkellers.

The second half does have its attractions – a seedy turn from Michael Robbins as a truck driver who makes a pass at Leiser, and a placid, reptilian turn from Cyril Shaps as the spy catcher hunting Leiser – but it’s a let-down.

In the book Leiser is an aging spy, past it and irrelevant, who takes the mission knowing it is doomed because he fools himself into thinking he has one last shot at glory, and who Anna takes up with in the hopes of escape to the West. Substituting him with a young matinee idol, and making Avery’s final speech about how the old sacrifice the young in war, is not a bad idea – and it’s very 1969 – but Jones is so painfully wooden, and the love affair with Anna so tedious, that it just doesn’t work.

The biggest problem with the film is its star, Christopher Jones. An American heartthrob who modelled himself on James Dean without having even one scintilla of his charisma, talent or screen presence, he pouts and sulks his way through the film as if he would rather be anywhere else. His performance was dubbed and somehow a viewing of this film convinced David Lean – who did not know his voice was dubbed – to cast him in Ryan’s Daughter. The filming was a disaster, Lean belatedly realised Jones couldn’t act, and Sarah Miles secretly drugged Jones while filming, which led to a car crash and a breakdown. The whole debacle killed Jones’ career and he never starred in a film again. One would be tempted to feel sorry for him, did not everyone who worked with him say he was a sullen, self-involved prick, and had he not violently raped Olivia Hussey around the time this film was made in, of all places, 10050 Ciello Drive. In a sad mirror of Leiser’s backstory, Hussey became pregnant with his child and had it aborted.

Another, lesser problem, is the score by Goon Show maestro Wally Stott. It’s light jazz and feels completely out of place. He throws in a little zither quite late in the film – because without some zither how would a 60s audience even know it was a spy film!? – but otherwise it punctures and deflates the tension rather than serving the narrative.

Pierson, who adapted and directed the film, went on to be an extremely successfully writer and producer, responsible for many terrific films – Cat Balou, The Anderson Tapes, Presumed Innocent, Cool Hand Luke, Dog Day Afternoon – but his directing career never really caught light.

In the end the film belongs to Hopkins, who is magnetic, burning up the screen, mesmerising and shrewd; it is worth watching the film for him alone.

Factor in all the turns from other wonderful character actors, and this is definitely worth your time. Just try and ignore the gaping whole in the middle of the film where a leading man should be.