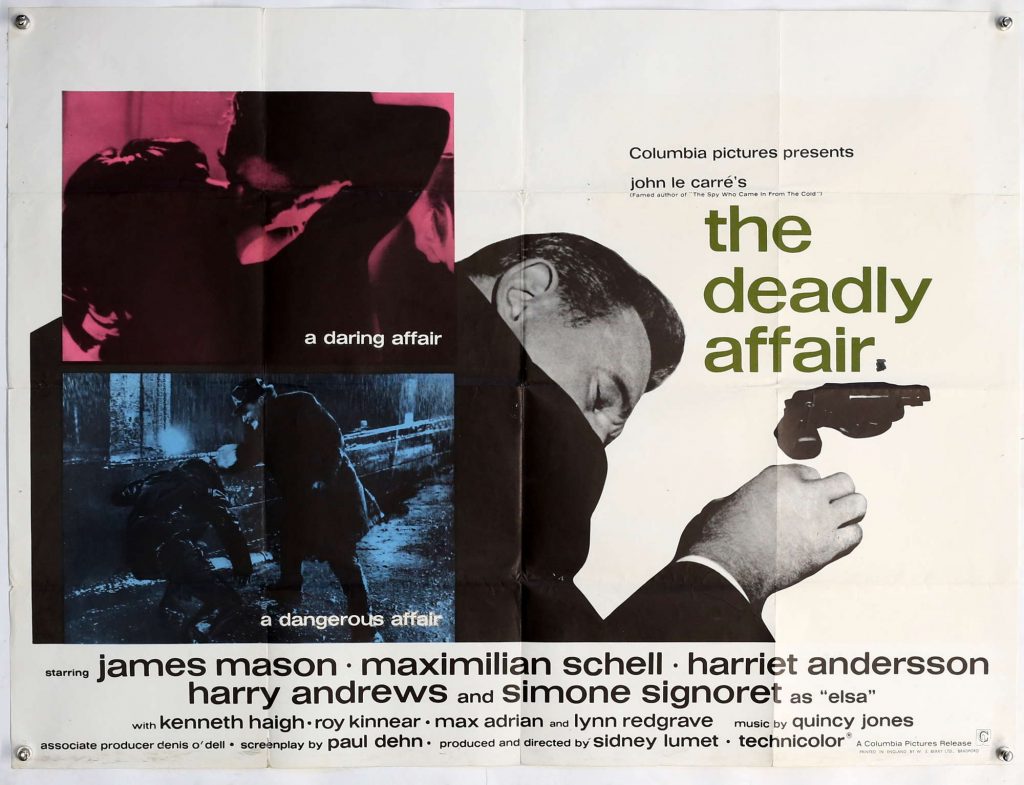

John Le Carré’s first novel, Call For The Dead, is a hybrid thing – a spy novel masquerading as a murder mystery, or perhaps a murder mystery masquerading as a spy novel. It feels appropriate that its genre is as slippery as a spy’s legend, but however you choose to classify it, it’s a thumping good read. The film version is, for the most part, extremely faithful to the source material.

John Le Carré’s first novel, Call For The Dead, is a hybrid thing – a spy novel masquerading as a murder mystery, or perhaps a murder mystery masquerading as a spy novel. It feels appropriate that its genre is as slippery as a spy’s legend, but however you choose to classify it, it’s a thumping good read. The film version is, for the most part, extremely faithful to the source material.

We open in St James’ Park, where Charles Dobbs (James Mason) is strolling up and down the bridge (from which I once leapt into the water to rescue a drowning cygnet while on my way to work, fact fans!) chatting with Samuel Fennan (Robert Flemyng).

Fennan, a Foreign Office employee, has been accused, in an anonymous letter, of being a spy for the Soviets; Dobbs, a spy, is conducting an informal interview to see if there’s any truth to the letter. He concludes there isn’t, but their conversation has been overseen. Later that night, Fennan apparently commits suicide. Dobbs’ superiors want to sweep it under the carpet and blame Dobbs for scaring the dead man, but Dobbs doesn’t buy it and begins to investigate the death.

The first thing to say is that Dobbs is, obviously, Smiley – in ’67 the rights to the character still rested with the makers of The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, who had cast Maigret’s Rupert Davies in the role two years earlier, so he was simply renamed for this film. I’m going to call him Smiley coz that’s who he is.

Spoilers for the whole film follow.

His investigation goes pretty much exactly as it does in the book, with Smiley interviewing Fennan’s wife, Elsa (Simone Signoret), and discovering that her dead husband had booked an alarm call for the morning after his death (the call for the dead). He then realises he is being surveilled, turns the tables on his pursuer, recruits retired detective Mendel (Harry Andrews) to help him, and eventually, despite being hospitalised, manages to work out what’s been going on, and bring the affair to a close.

Meanwhile Smiley’s wife, Ann (a badly dubbed Harriet Andersson), has taken Frey (Maximilian Schell), an old friend of Smiley’s, as her new lover (the deadly affair), which derails Smiley’s placid domestic equilibrium.

The screenplay is by Paul Dehn, hot from Goldfinger and The Spy Who Came in from The Cold, and who would go on to write all four of the brilliant Planet of the Apes sequels (yes, you read me right, they’re all brilliant, don’t come at me). It’s a lovely screenplay, with terrific snatches of dialogue, as evidenced by this poignant speech from the doomed Fennan, as he explains why he was a communist in the 30s:

When you’re young, you hitch the wagon, or whatever you believe in, to whatever star looks likely it can get the wagon moving. When I was an undergraduate, the wagon was social justice, and the star was Karl Marx. We perambulated with banners. We fed hunger marchers. A few of us fought in Spain. Some of us even wrote poetry. I still believe it was a good wagon, but an impractical star. We had faith and hope and charity. A wrong faith, a false hope, but I still think the right sort of charity. Our eyes were dewy with it, dewy and half shut.

The director is Sidney Lumet, a true master who had already made Twelve Angry Men and The Hill, and who was just beginning to really hit his stride. He keeps the tension up and shoots the film with dynamism and movement, especially when he goes handheld for the scene when Mendel beats up a dodgy car dealer (a vibrant, seedy turn from Roy Kinnear).

Mason is a brilliant Smiley – a man confused about what kind of man he should actually be, bubbling with energy and anger yet with nowhere to put it. His work want him to go with the flow, which he refuses to do, and his wife wants him to fight for her, which he is just too accommodating to consider. His wife is as confused by him as he is by himself.

Ann: How can you be so aggressive about your job and so gentle about me?

Charles: I’ve always thought that being aggressive was the way to keep my job, and being gentle was the way to keep you…

To his bewilderment, Smiley loses both job and wife but then, freed from the bonds that restrain him, he finally comes fully alive, allowing himself to be wholly consumed by the hunt. He is a puzzler and a hunter, who realises that he has compartmentalised himself too completely, that he must mix his aggression and kindness into both spheres of his life to achieve balance.

His kindness to the real spy – Elsa – is matched by his fury for her handler, the man who stole his wife, Frey. When he savagely clubs his old friend around the head with his plaster-casted hand, he’s almost animalistic and primal; when Frey, clinging to a muddy dock, tries to climb out, Smiley stamps on his hands and watches as he’s crushed by the boats on the tide. Only then, his fury spent, does he cry out his friend’s name, seemingly horrified at what he has done. It’s electric stuff. And at the end, he flies off to reclaim Ann, willing to fight for her at last.

There are other wonderful performances here, but special mention must go to Simone Signoret, who is given two intense scenes with Smiley; she is astonishing as a woman who survived the concentration camps but who perhaps left too much of herself behind in them.

One of the unexpected joys of the film comes in the final act, when Smiley and co spring a trap for Frey and Elsa at the theatre. Lumet stages this sequence during an RSC performance of Richard II, and we get to see a chunk of Peter Hall’s production on screen. This includes the amazing David Warner playing Richard’s gory, upsetting death scene – hot poker and all. Even though he’s on the screen for a short time, Warner is magnetic. It’s so good, in fact, that I kind of wanted to keep watching that and was a bit miffed when the action kept switching back to Smiley and co. If only Lumet had decided to film the whole performance, just for fun, while he had the actors there.

Anyway, this is a much, much better film than The Looking Glass War, but it falls short of The Spy Who Came In From The Cold because Dehn makes one fatal tweak to the book.

In the source material Ann runs away with a Cuban race car driver, but in the film the appeal of having Ann’s lover be the spymaster Smiley is hunting is too much for the writer to resist. But it’s too neat, too narratively symmetrical, to sit easily with Le Carré’s world of murky morality and slippery motives. It’s also a blindingly obvious twist, especially because the title of the film is a huge spoiler. Additionally, it requires some scenes at the start of the film to make the affair more central to the film’s plot, and while this works in some ways, the scenes themselves feel overwrought and uncomfortable, as if cut from an ersatz adaptation of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolff? and slapped into a cold war thriller where they really don’t belong.

Another problem is the much lauded score by Quincy Jones, which mostly just keeps layering bossa nova over the film. Despite occasionally deeming to underscore some tension, it feels like a score written because it would make a good album, not because it is appropriate or sympathetic to the film. It may be a good LP, but it’s a terrible accompaniment to the pictures. But lots and lots of people disagree with me, so YMMV.

These niggles aside, this is a watchable, exciting thriller – a cut above the average, with flashes of genuine greatness.