When I was young, I probably read between 3 and 5 books a week. I was voracious.

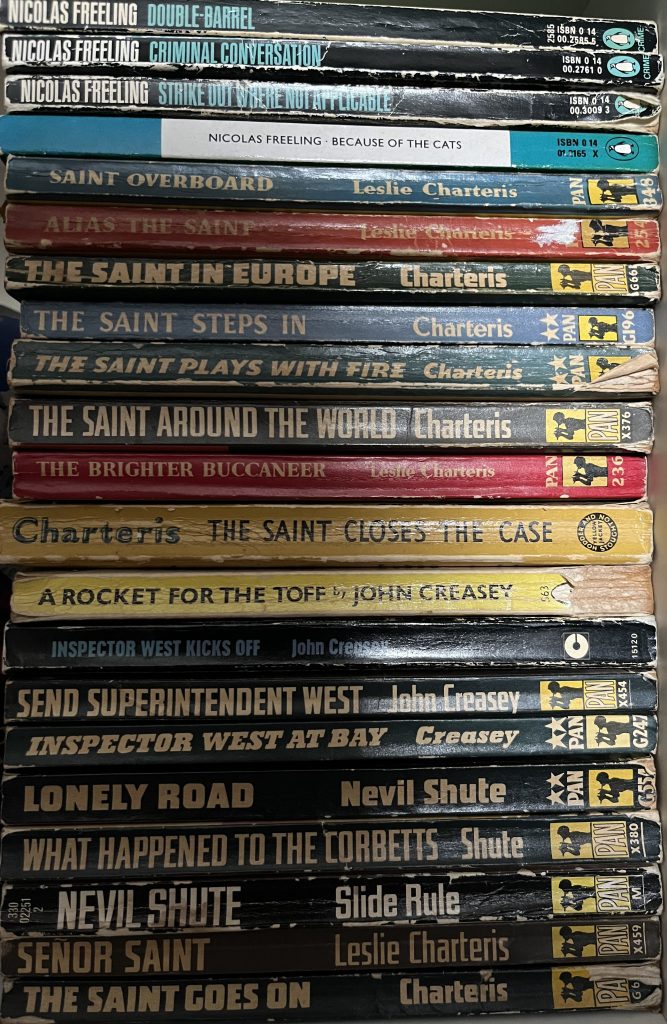

My tastes were catholic but I followed my father’s lead an awful lot, and many of the books I read were by authors he had enjoyed in his younger days. He pressed on me The White South by Hammond Innes, No Highway in the Sky by Nevil Shute, The Bafut Beagles by Gerald Durrell, the Van der Valk thrillers of Nicolas Freeling and, my father’s abiding passion, Georges Simenon’s Maigret books. Being a completist at heart, I devoured every book by each of these writers (Simenon excluded – there were just so many!) before I was 15.

He guided my comic reading too, happily paying for a weekly subscription to Victor – ‘True Stories of Men at War!’ – but turning his nose up when I suggested he might do the same for the significantly more enticing 2000AD.

This gave my reading an out of time quality, marking me out as slightly old-fashioned even before I was out of short trousers.

My father, who endlessly drove the length and breadth of the country to play gigs in folk clubs big and small, had a map of the country in his head, and each secondhand bookshop was clearly marked. Before we embarked on any trip at all, he would know without having to check if there was a secondhand bookshop we could drop into on the way. There usually was, they were so ubiquitous in those days.

Normally he indulged me, encouraging me to pick up any books I fancied. Browsing musty bookshelves was one of the few activities we shared as I grew up, his passion for football not having been passed on to me, and my passion for science fiction TV not meeting the high intellectual and artistic standards he set for himself.

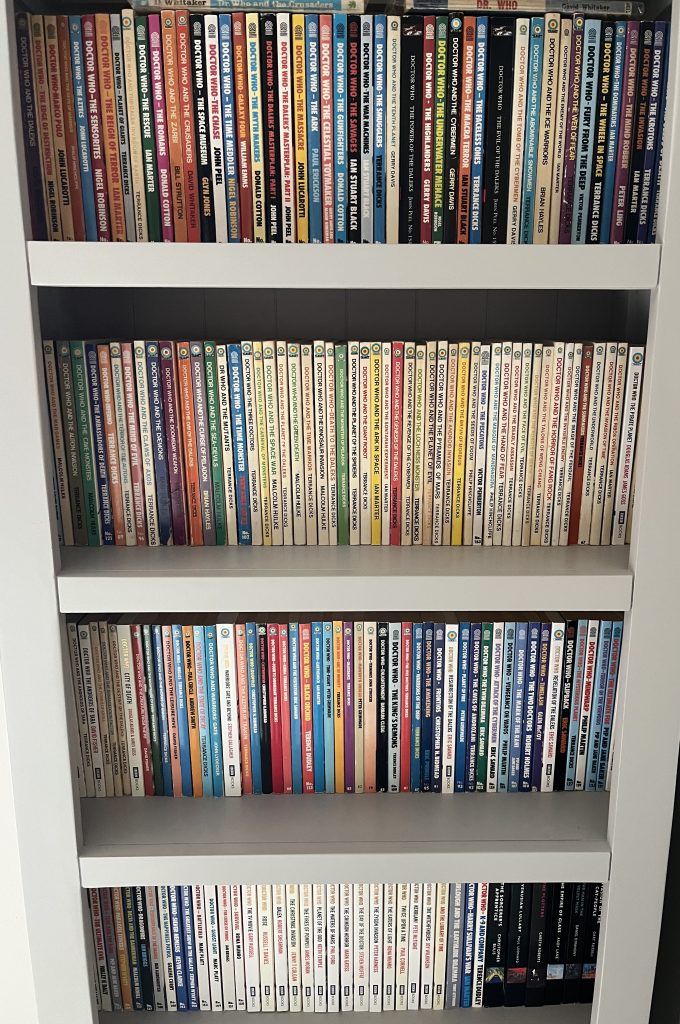

(This led to an incident that still burns to this day, when I found a mint condition copy of the extraordinarily rare 1970 Doctor Who annual for a mere £10 in a small village shop sometime in the 80s. I had the money at home but not on me, but he refused to lend it to me because Doctor Who was ‘silly’. I have never, to this day, seen a copy of it on sale in the real world again.)

Dad inherited this passion from his father, with whom he’d spent many happy days bookshopping, a ritual that his mother found inexplicable and upsetting – once she secretly baked their day’s haul of old tomes in the oven, trying to rid them of germs and filth.

Once every 3 months or so, Dad and I would engage in a ritual cleaning out of our libraries. We would take the tottering pile of books we had read, pick out any we thought we wanted to keep and maybe reread – very few – and then pack them all into boxes, making sure to keep our book separate. Then we took a trip to Stoke-on-Trent, and a fusty old secondhand bookshop.

Just inside the door was an old table behind which sprawled a kindly middle-aged chap with a pipe hanging from his lips. The whole shop, and all the books that we brought home from it, were infused with the warm brown odour of sweet tobacco. A black lab lay under the table at his feet, old and genial, it raised its head from its paws in greeting, gave a lazy wag of its tail, then dropped back to dozing.

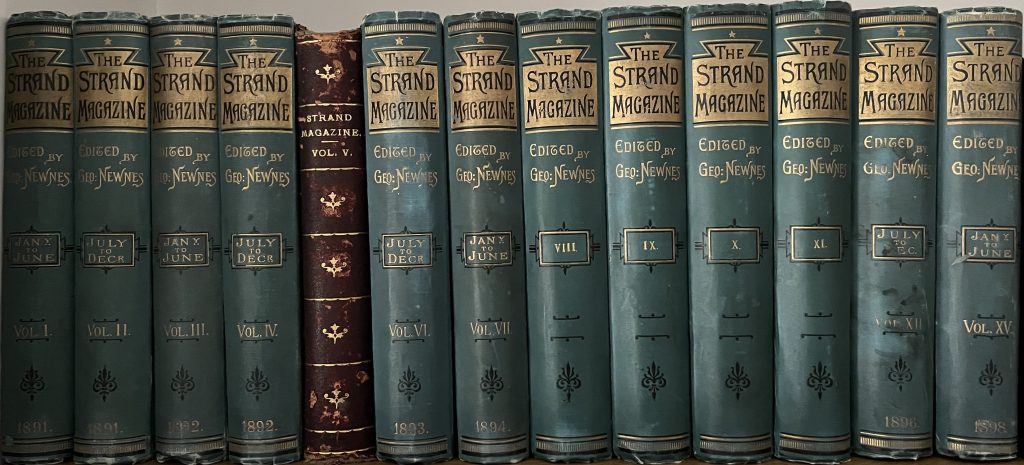

We would hand over our boxes and while the shopkeeper went through them, marking them up in pencil on a scrap of paper, we would browse for gems on the shelves that stretched deep into the shadows at the back of the shop. I was normally hunting for old Penguin editions of John Wyndham, Pan editions of Shute or Innes and, of course, any Target Doctor Who books that I’d not yet tracked down.

When we had finished browsing we’d return to the shopkeeper, he would tell us how much he’d give us for our books, subtract the cost of the ones we had picked out, and we would pocket the difference. Then, if Dad was feeling indulgent, he’d let me pop to the sci-fi bookshop in the nearby shopping mall, where I would spend my cash on lots of assorted Doctor Who stuff.

It was a beloved ritual, somehow timeless, and a thread that tied together 3 generations of Andrews men. I can still remember the day we went with our boxes to find the shop closed and shuttered. An anchor in our lives pulled loose and lost.

In the years that followed, my relationship to my library changed.

Aged 8, I was sent to boarding school. I no longer had a room of my own, just a cubicle, and no room for a bookcase or even a shelf on which to keep a pile of books. I could have 1 or 2 at a time from the school library, but that was all.

I felt lonely and insecure in that place, stripped of safety, vulnerable. It was many, many years before I finally had a proper room of my own again and I realise now that in order to create a sense of security for myself, I began to line the walls with books, as a bulwark and a cocoon. I didn’t winnow out the books I had read any more, I stacked them high and used them to create a sense of ownership. This space is yours, they said, and you are protected within it. This is not boarding school, you are free.

I had become a bit of a hoarder and it is a hard, hard habit to break. To this day, there are books I have been lugging around with me for upwards of 20 years that I have not yet read and almost certainly never will, and others that I read and didn’t particularly enjoy, but there they sit on my shelves, talismanic of freedom.

I have noticed that at times when I feel most anxious and insecure, I go on buying sprees and begin new collections. It’s no coincidence that straight after the break-up of my marriage I began a truly quixotic quest to find a copy of every potboiler written by the grotesquely prolific John Creasey – there are more than 600, and no definitive list exists, he used so many pseudonyms. Happily, I eventually saw sense.

Recently, having become aware of my patterns, I decided it was time to resume my practice of bundling up my read books and cleaning out my library every so often. So I dutifully took a couple of boxes to the secondhand bookshop in my town. I like it there, they have a good collection of old annuals, and I was thinking that I could use my earnings to pick up some old Victors and enjoy a pleasant evening reading Tough of the Track. But instead of a genial shopkeeper happy to make me an offer on new stock, I found a young man who was entirely bewildered by me.

‘Oh, we don’t buy books,’ he said, looking at me like I was stupid.

‘But you’re a secondhand bookshop, how else do you get stock?’

He shrugged. Then, as I was picking my boxes back up again and moving towards the door, he said ‘You can always donate them to us, of course.’

‘You’re a business,’ I replied, incredulous. ‘Why would I donate to your profit margin?’

He shrugged again and decided to ignore me.

And so now I am sat at home with a box of books that hover in limbo. I know I could just donate them to the charity shop of my choice, but somehow that sticks in my craw. I want the exchange, the barter, the browsing. I suppose I really just want the experience of being a young child again, in a room of warm smoke and old books, hunting for treasures.

That, of course, is impossible.

So the Oxfam bookshop will probably soon be the recipient of a fine collection of clothbound McSweeney’s – relics of a collection that I spent a fortune assembling during a prolonged panic attack 20 years ago but never read because I eventually realised that, while the books themselves were beautiful objects that brightened my shelves, I don’t actually much care for contemporary American literary fiction.

I no longer require the illusion of safety that their presence on my shelves used to represent.

It’s a start but, oh my, there are so many more books still here…