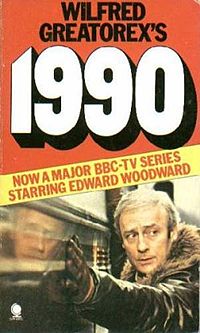

Some years ago, browsing through a second hand bookshop, I stumbled across a TV tie-in book for a show called 1990. I was instantly intrigued.

Some years ago, browsing through a second hand bookshop, I stumbled across a TV tie-in book for a show called 1990. I was instantly intrigued.

A BBC drama starring Edward Woodward as Jim Kyle, heroic leader of a resistance movement in totalitarian Britain? How is it that I had never heard of this show? And how could I see it?

Amazingly, for reasons long forgotten, I didn’t buy the book, but recently, after years of searching I finally got my hands on the series.

Created by one of TVs great unsung heroes, Wilfred Greatorex, it ran on BBC2 for two season of eight episodes broadcast in 1977/8. But although 1990 was on at exactly the same time as Secret Army, a show with which it shares many similarities and themes and on which Greatorex was a creative consultant, it has aged far less well.

The first problem is Gretorex’s opening two parter. It’s strong on character and ambience but frustratingly free of details. Who are the totalitarian rulers, how did they come to power, what are their objectives, how do they exert control? It’s only over the course of the first eight episodes that the details are, sparsely, pencilled in, and then it’s done so piecemeal, by different writers, that it’s hard to extract a definitive statement.

But as the picture clears we are presented with a very sub-Orwell collection of oppressors.

In the series’ fictional timeline the Unions have brought the country to a standstill. The economy has totally collapsed, and a strong arm, union-led left wing government has taken power. No one can work, buy food or be housed without union cards and authorisation. A three day week has been imposed and having more than one job is illegal. Also, everyone has to sign a form declaring that they will not leave the country for ten years after they graduate, thus preventing a brain drain.

If you transgress one time too many all your cards are revoked and you join the 80,000 non-people living rough on London’s steets as a warning to the rest of the populace.

People make impassioned speeches about just wanting to pay their own way, and being criminalised for getting on their bikes and cleaning windows on rest days, and at one point Kyle sympathises with the poor landed aristocracy who’ve been turfed out of their crumbling piles. It’s not hard to conclude that Greatorex voted for Maggie.

The vision of a union controlled sub-communist future must have seemed ultra relevant to audiences bracing themselves for the winter of discontent. Now it seems almost quaint.

Prisons are largely obselete, with most punishments consisting of a month or two being forced to take ‘misery pills’. Racism against black people is also a distant memory; now it’s the Aussies and other former colonials who are despised, although it’s unclear exactly why.

Public order is maintained by the Public Control Department (PCD), a civil service dept working for the Home Office; essentially they are a bunch of bully boys monitoring and surveilling the population, keeping people in line with intimidation and bureaucracy.

As the series opens the PCD has set up a series of Adult Rehabilitation Centres (ARCs), to which dissidents will be sent for ‘treatments’. They’re frequently referred to by Kyle as Concentration Camps, but they’re portrayed as little more than rest homes where the worst the inmates can expect is a few drug treatments and bit of electric shock therapy designed to make them docile. All very Clockwork Orange, but hardly terrifying when stacked up against Auschwitz.

You see, the PCD are completely inept.

Their method of bugging people involves dropping pill-sized transmitters into jacket pockets, presumably on the assumption that people never put their hands in their pockets any more. This laughable ineptitude is often commented on by the heroes, and it robs the villains of their power, making them seem like bumbling twits. Kyle consistently eludes his overseers by taking his bug out and dropping it someone else’s pocket. What cunning!

Even worse, in one episode the PCD concoct a speech by editing together video of a person speaking to camera recorded on different days. Their continuity person is so bad that a pocket handkerchief appears and disappears throughout the speech, exposing their ruse and again, making them seem like utter planks.

When we do see the PCD putting the frighteners on people they’re similarly unthreatening. Yes, they provoke one poor woman to miscarriage, but not by beating her up or trashing her apartment – they simply pretend to have been bitten by her dog, which they take off to the vets as a ‘danger to public health’; they’re as gentle as Tristan bloody Farnon. In one episode they ever so politely shove a man aside and knock a few books off his shelf, and in another they rip the floorboard up in a house… and refuse to nail them back. The rotters!

All TV is state controlled, and all but a handful of newspapers are similarly trammeled. Our hero is Jim Kyle, a crusading journalist working for the last independent newspaper, trying to smuggle the truth into print whenever possible. In one episode the PCD fail to stop him getting hold of a big story but the typesetters union refuse to set it, as they consider it anti-government.

BIG problem here: totalitarian states do not tolerate crusading independent journalists. They vanish them. Kyle’s very existence de-fangs the enemy he stands against – if they were such a formidable threat they’d just shoot him in the back of the head and dump him at sea. Or feed him polonium. The show is flawed in its very core.

Kyle’s also, more interestingly, a modern Pimpernel, smuggling people out of the country at great risk, refusing payment no matter how many times it’s offered.

While the protagonists of Lifeline were risking life and limb over on BBC1, Jim Kyle was doing much the same thing on BBC2 except without any real sense of tangible threat or, tellingly, much of a budget. Secret Army could shoot exciting action and location sequences, 1990 is largely studio-bound. So much so that, in one unintentionally side splitting scene, Jim Kyle walks and talks for three whole minutes during which he barges through the same door and pauses to declaim in front of the same beige flat no less then EIGHT times in a row.

When they do leave the studio the show gets more fun. A sequence where Kyle and his buddy Tony Doyle, later to be so marvelously menacing in Between The Lines, sneak into an ARC to expose the Dr Mengele type goings on therein, is exciting but it only highlights how rarely such thrills occur. And the episode in which Kyle drives around London in a covert camper van is… well, words fail.

Woodward is, predictably, bloody brilliant. Kyle is witty and urbane, outraged and crusading yet with a deep cynicism and world weariness. But I can’t help wishing he were given more punching to do. And running and shooting and all the things he did so well in Callan. Not because I want him typecast, but because the series desperately needs the injection of excitement that would bring, and god knows if you want a bit of thrilling violence then Woodward’s your man.

How much fun to contrast his urbane public face with his lurking hardman, to highlight the double life he lives starkly, moving from press conference to nighttime smuggling operation, and back again, to explore the character of a man fighting the system with both his intellect and his fists.

But despite flashes of this, Woodward’s never quite given the opportunity to take the character anywhere genuinely interesting. I think, because 1990 was on BBC2 it seems almost wilfully determined to avoid anything as lowbrow as genuine excitement. ‘This is about ideas and themes, not entertainment,’’ says the show. But the same ideas and themes were being explored much more potently on the more mainstream parent channel, because Secret Army was able to conjure a real sense of threat that brought home to the viewer just how high the stakes really were in a way that talking about it in well-lit rooms just doesn’t.

So we have an inept enemy, bullying and bureaucratic but never really menacing or scary; a hero whose very existence beggars belief, and a show that is hidebound by both budgetary constraints and its own misplaced aspiration to Play For Today seriousness instead of primetime excitement.

What, then, is to recommend this?

Well, it’s so NEARLY brilliant. The premise has enormous potential that every now and then flowers into moments of genuine crusading outrage. Woodward is never a chore to watch. Also the central relationship between Kyle and PCD Deputy Controller Barbara Kellerman is fascinatingly complex and watchable. She smoulders and flirts but terrifies at the same time, and the mix of fascination and repulsion that she inspires in Kyle makes her a uniquely fascist femme fatale.

And finally, finally, in the last two episodes things start to become credible. Kyle is made the subject of a show trial, and then, when that fails, all his cards are revoked, he’s turned into a non-person and forced to scavenge on the streets to stay alive. Suddenly the show has become gripping, the enemy has shown their teeth and the hero is genuinely threatened. Things start to feel a little bit real.

The subplot of the finale is good too, as the PCD come up with a unified ID system, doing away with ration cards, identity cards, driving licenses et al, and combining them in one document designed to put an end to the black market but which, brilliantly, is so easy to forge that it brings down the economy. Again. It’s the first time this vision of the future feels genuinely prescient.

Unfortunately it all gets fumbled in the final minutes, when Kyle manages to blackmail the PCD into restoring his citizenship and a big reset button is hit that completely undoes the previous two hours of top telly, but for a while there you could see how good this show was capable of being.

I can’t help feeling that the first six episodes could have been dispensed with entirely, and the two part finale would have made a gripping opening, establishing the nature of the threat starkly and believably (minus the cop-out ending).

Then you have a show re-conceived, with a forgotten hero, a non-person, already made an example of, living outside the system, always trying to stay one step ahead of the authorities, perhaps running a secret Lifeline, living two or three or four different lives simultaneously. How exciting that would have been.

Oh, wait a minute, that was the Blake’s’s Seven pilot.

Or was it Secret Army?